Never Give Up

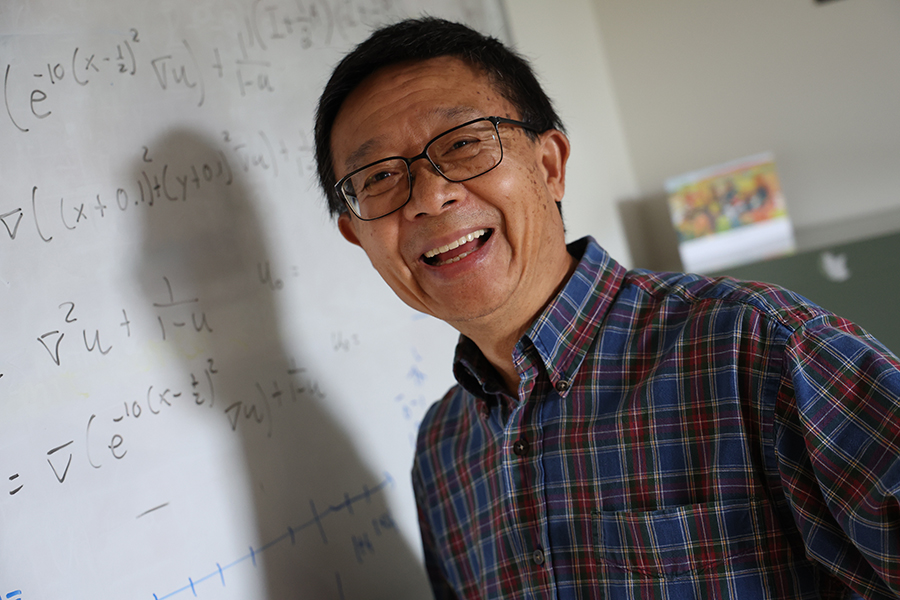

Although Baylor mathematics professor Tim (Quin) Sheng wasn’t technically considered a first-generation college student because both his parents had taken part in higher education, the obstacles he had to overcome to achieve a college degree in a time of oppression in communist China were daunting.

Dr. Tim Sheng wasn’t allowed to study physics when he enrolled in college. The reason could possibly be traced back to his parents, who had just recently ended a decade imprisoned in Communist Chinese reeducation camps, but had even more to do with a distant relative who died in China in 1916, some four decades before Sheng was born.

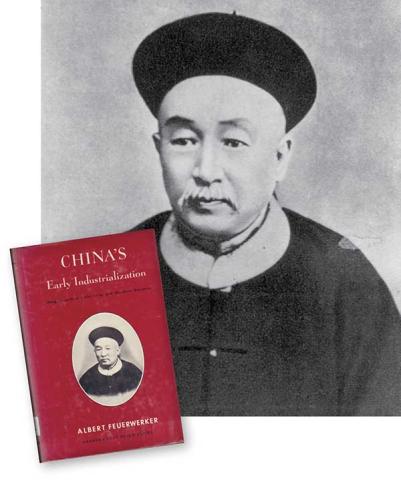

That relative — Sheng Hsuan-Huai — was an entrepreneur in the final years of the Qing Dynasty in China, which ended in 1912. He was a leader of the initial industrialization and construction of more than 14,000 miles of railroad line for the country. He established national banks and universities, and he founded the Chinese Red Cross. As befits such a powerful, important figure in history, in 1958 Harvard University Press published a book about him — “China’s Early Industrialization: Sheng Hsuan-Huai and Mandarin Enterprise” — which has been reprinted several times.

In 1978, when Tim Sheng was admitted to China’s Nanjing University, one of the top research universities in Asia, he was interested in studying physics — particle physics in particular. But when he got to the registrar to enroll, “the guy looks at me and says, ‘No way, you cannot be a physics major,’” Sheng said, and he was immediately directed to mathematics instead.

Only much later did Sheng learn that the reason that he could not be allowed into physics, his program of choice, was because of his family name. His parents, and his relatives dating back to Sheng Hsuan-Huai, were educated individuals. Because of this fact, in the People’s Republic of China they were classified as enemies of the people, and therefore had to stay away from the study of real sciences or risk being forced into heavy labor. According to this reasoning, making sure Sheng studied mathematics instead of physics would reduce the risk level for the country.

“So that’s why I could not do physics. It’s Sheng Hsuan-Huai’s fault. I should change my last name,” Sheng said, laughing.

Tragedy and its aftermath

The fact that Sheng even made it to college at all is nothing short of a miracle.

Sheng’s father was a civil engineer and his mother was a physician, which made them among the millions targeted by the country’s leader, Mao Zedong, as he launched what was known as the Cultural Revolution in the mid-1960s. The movement had the stated goal of preserving Chinese communism by purging what capitalist and traditional elements might have remained from pre-communist society.

On a day in 1965, when Sheng was about nine years old, his parents left the family home for work and did not come back. They were forced into hard labor in remote reeducation camps, and stayed gone for 10 years. In the camps, Sheng’s mother cleaned toilets for that decade since the Red Guards considered it a special torment for a doctor to endure. Sheng doesn’t know the type of work his father did in the camps, but does know that he suffered two broken arms and two broken legs during that time.

Left without their parents, Sheng and his younger brothers, who were six and seven at the time, went to live with their grandmother in Suzhou, a major city on the east coast of China more than 1,000 miles from their hometown in Hunan Province.

“When I was in third grade, the schools closed. No schools existed in China for about eight years. No elementary school, no high school, no middle school. Nothing.”Dr. Tim Sheng

“My grandmother was not educated at all. She could hardly spell a word, and we didn’t know what to do and had no income,” Sheng said. “We sold our furniture and calculated every penny for food. We just maintained the minimum level of living. Of course, everyone on the streets could insult us since we had the family name Sheng.”›

The family lived on vegetables that they grew or were given, and rice, which was strictly rationed. They occasionally got some eggs — maybe once a year — and never had any meat. And school was out of the question.

“When I was in third grade, the schools closed,” Sheng said. “No schools existed in China for about eight years. No elementary school, no high school, no middle school. Nothing.”

A burning desire to learn

But Sheng and his brothers still had a desire to continue learning, and they did so with a little thievery.

Book burnings were common evening practices by communist Red Guards in Suzhou, so Sheng and his brothers would sneak out of their grandmother’s home, steal books that were destined for the fire, take them home and start reading. They read together and discussed what they didn’t understand, which was quite a bit. They would piece together the parts of the literature books that they could comprehend, and then make up the rest of the story. The brothers hid the books so well that they survived the revolution — even when all of their family photos were found and burned by the Red Guards.

When Sheng and his brothers got interested in subjects including physics, math and chemistry, “we tried to figure out something, then whenever we got a chance to meet someone safe — relatives, neighbors, whoever had knowledge and kindness — we could ask them,” he said. “But all these must be done stealthily, since once caught by the government, severe consequences might follow.”

“Because of my past experiences, I feel more motivated and obligated to go the extra mile in assisting students who are first-generation.”Dr. Tim Sheng

When Sheng was about 18, his parents were released from their labor camps and reunited with their sons. It was a somewhat awkward reunion because he and his brothers knew nothing about their parents’ situation at the time, as there had been no communication between them over the years.

“And then suddenly, they appeared,” Sheng said. “Two strangers, and they said, ‘We’re your parents.’ That’s also the tragedy. Three boys and their parents didn’t know the other side. We grew up and never saw or heard from them. There wasn’t even a family photo to look at.”

Chinese schools slowly began to reopen in 1973. Sheng would attend school for half a day and then do factory work for the other half. He did that through high school, and after graduation, since the colleges had not yet opened back up, Sheng took a job ironing clothes eight to 11 hours a day in a manufacturing facility. At night, he continued to study algebra, physics, chemistry and English on his own. He also continued living with his grandmother.

Going to college

In 1978 when colleges in China suddenly began to open, Sheng applied along with 5.7 million other young people in the country. Strict entrance exams were enforced, and the official national college admission rate was only about 4.8 percent that year, Sheng recalled. He and his brothers all passed their exams, so at 22 Sheng began at Nanjing University majoring in mathematics instead of physics.

“Doing mathematics is not dangerous to the government and not dangerous to the country. Not to the people,” he said. “If you do physics, it can be different. Say, you can do nuclear physics.”

Sheng went on to earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mathematics at Nanjing. Then, since there was no doctoral program in China at the time and the country was changing — “The door was opening at that time, slowly,” he said — he applied to several overseas institutions including Cambridge University, where he chose to begin doctoral studies in mathematics. His studies were generously sponsored by the Schlumberger Foundation and the British government.

When Sheng prepared to leave China for his trip to London, his master’s degree advisor approached him and secretly gave him $100 — money the advisor had hidden in a suitcase for more than 36 years since, at the time, possessing foreign currency was a felony in China. That $100 became the only hard currency Sheng had to begin his endeavor in England.

While at King’s College, Cambridge, Sheng met Dr. Amos Koo, a Korean pastor and visiting scholar, who introduced the young graduate student to Christianity.

“Through his introduction, I got my first Bible and became a Christian,” Sheng said. “My faith has been guiding me in my continuing endeavors for research and knowledge in mathematics and physics. It is the eternal fire that has lighted up my life.”

“Be responsible and never give up has been my motto.”Dr. Tim Sheng

Sheng finished his PhD in mathematics in three years and then spent a year of additional study at Arizona, Stanford and MIT in the United States. He then taught at the National University of Singapore for five years and at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette for another five.

In 2005 Sheng joined the Baylor faculty as a professor of mathematics and a faculty member in Baylor’s Center for Astrophysics, Space Physics and Engineering Research (CASPER). He also serves as an editor-in-chief for a prestigious research periodical, “International Journal of Computer Mathematics,” published by Taylor & Francis in London.

“Never give up”

Sheng’s youngest brother died many years ago due to poor health, but his surviving brother went on to earn a PhD in chemistry in France and now lives in Australia. The two brothers used to visit their parents, who are now in their 90s, every couple of years, but the family had gotten together even more frequently in recent years until the COVID-19 pandemic broke out and prevented those meetings.

Despite the challenges that his family situation presented him with, Sheng said his desire to pursue the truth in nature has always inspired him to overcome hardships.

“Be responsible and never give up has been my motto,” he said.

Sheng said his past experiences have helped him understand others who are vulnerable in some way because of their backgrounds.

“It also encourages me to do better in teaching and research, and to help those who are not so fortunate as compared to many others,” he said. “Because of my past experiences, I also feel more motivated and obligated to go the extra mile in assisting students who are first-generation, or who are minority or underrepresented, as they seek higher education.”